As previously mentioned on this blog, the International Court of Justice (“ICJ” or the “Court”) was presiding over a maritime territory dispute between Peru and Chile. In the action, titled Maritime Dispute (Peru v. Chile), the two neighboring South American coastal nations were fighting over their maritime boundaries. The Law of the Sea allows for 200-nautical mile exclusive economic zone (“EEZ”) seaward from the coastal baseline. The problem facing Peru and Chile is that their coast formed a V-shape – meaning that the 200-mile zones overlap.

Chile brought the case to the ICJ, asking the Court to split based on the equidistance mark. Chile, however, contended that the two nations had previously reached an agreement, and that the Court should enforce said agreement. The Court, in its decision, announced in late January, found that there was an existing agreement in place, the 1954 Special Maritime Frontier Zone Agreement (“1954 Agreement”); however, the agreement did “not indicate when and by what means that boundary was agreed upon” and that the agreement gave “no indication of the nature of the maritime boundary.” The Court then found, based on previous declarations made by the nations, that the nature of the boundary was all purpose, meaning it included both the water and the seabed. The Court also noted that at the time the agreement was made, there was no international recognition of a 200 nautical mile boundary, and as such the parties could not have been contemplating one at the time. Taking into consideration the fishing norms at the time of the 1954 Agreement, the Court concluded that the agreed maritime boundary extended 80 nautical miles.

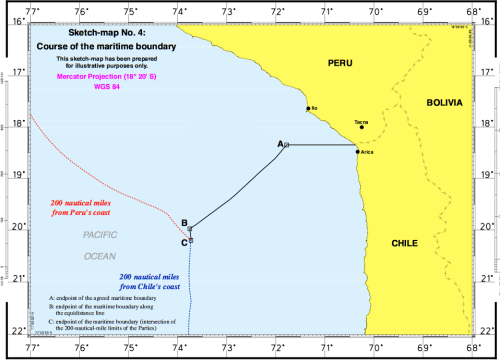

Taking all findings into consideration, the ICJ drew the boundary line by extending out, parallel of latitude, 80 nautical miles from the Chile/Peru land intersection. From that 80-mile point (Point A on the diagram), it then used equidistance to split the remaining portion of the EEZ, by making a southwest moving boundary line until it was beyond Chile’s 200-mile radius (Point B).

Do you think this was the right approach by the ICJ? Should the Court have used Peru’s equidistance proposal? Should the ICJ have relied so heavily on the 1954 Agreement which Peru did not believe was binding?

Source: The International Court of Justice

Photo Source: Maps on the Web

When two country’s exclusive economic zones overlap in the Sea, precedent cases say that the equidistant line is not always the appropriate place to separate zones. The main factor in determining the suitable place to separate the maritime territories is the coastal length of each country. Generally, the country with the longest coast is given a larger mileage. In other past maritime dispute cases, different elements, like population and reliance on the sea, are also taken into consideration. No matter what the circumstance, a country must also have an open path from their country’s coast to open sea for defense purposes.